"My family didn't want me to go back to the front line": the story of a soldier released from Russian captivity in a controversial Hungarian-sponsored scheme

Roland, 25, is a soldier in the 128th Separate Mountain Assault Brigade. He comes from Mukachevo, a city in Zakarpattia (Transcarpathia) in Ukraine's west, and his name reflects his Hungarian origin. Roland's surname is pure Hungarian – it means "tanner" and is a very common name in Zakarpattia.

Roland was captured in June 2022 while serving in another brigade and spent an entire year in Russian captivity. He and ten other soldiers were later released as part of an initiative by the Hungarian Charity Service of the Order of Malta in cooperation with the Russian Orthodox Church. This release of a group of Ukrainian prisoners of war without any coordination with Ukraine caused a public outcry.

Several of the released soldiers later spoke to the media on condition of anonymity, but Roland is the only one who has spoken openly about how it all happened.

"I was ordered to go to a nearby wood. It turned out to be crawling with Russians"

Roland grew up in a mixed-ethnicity family, which is very common in Zakarpattia. His father is an ethnic Hungarian whose native language is Hungarian, and his mother is Ukrainian. Roland also spoke Hungarian fluently as a child, but he went to a Ukrainian school, and over time his Hungarian faded somewhat, although he can still have a conversation about simple topics. Neither Roland nor his father are Hungarian citizens, although they could have obtained citizenship had they wished. Roland considers himself Ukrainian, and Ukrainian is his native language.

In 2020 Roland signed a three-year contract with the 10th Separate Mountain Assault Brigade and became an infantry fighting vehicle (IFV) driver-mechanic. He took part in the Joint Forces Operation in Donetsk Oblast, where firefights with Russian forces flared up from time to time. In the first few days of the full-scale invasion, his unit was sent to the border with Belarus, and when it became clear there would be no attack from that direction, they were redeployed to Kyiv Oblast.

"We were holding the defence and repelling Russian assaults; I was fighting as an infantryman with a rifle," Roland recalls.

Later the brigade was sent to Luhansk Oblast. In June 2022, Roland's unit was positioned at the junction with a neighbouring military unit to prevent encirclement by the enemy.

"I was on duty at the observation post, then my brother-in-arms and I went to get some rest. I woke up to loud explosions nearby. I went back to the observation post, but the commander ordered me to go to a nearby wooded area, wait for an IFV, replace the driver-mechanic, and drive the guys to a safe place."

Roland ran across an open field and went into the nearby wood. It turned out to be crawling with Russians.

"Our old dugouts were full of the f**kers, and I walked right into them. They immediately took my weapon and tied my hands. Apart from me, there were around 15 other prisoners from the brigade next to us who had also been captured unexpectedly because they didn't know the enemy had advanced so far. I noticed that not all the Russians had helmets, and they had no body armour vests at all. One of their mechanics hit me in the face several times, but then someone senior shouted: 'Don't touch the kid!' (I was 22 at the time)."

Roland admits that for the first few minutes he was in shock. As a soldier he accepted that he might be killed or badly wounded, but he had never even theoretically considered the possibility of being taken prisoner.

"Then they led us through the village to their headquarters, and on the way I saw the IFV I was supposed to meet in the wood. It was on fire – it never got to the turn into the field, it was a few dozen metres short of there. Judging by the damage, the driver-mechanic definitely didn't survive. I don't know about the other guys."

There were about twenty other Ukrainian prisoners at the headquarters. Everyone had their trousers cut open along the back seam and their boots taken away (probably so they would not try to escape).

"The lad standing next to me was from the same region as me, and at one point they led him off 'to be executed'. But they only shot him in the leg, and then they started bandaging it, recording it on video and saying they were giving medical aid to a wounded Ukrainian who had surrendered. They hit me on the head several more times and fired a burst from an assault rifle next to my ear. When they were writing down our personal details, they asked me again: 'What kind of a name is that?' I explained I was from Zakarpattia. 'Ah, a Hungarian!..' It was lucky I didn't have any ID on me, because if they'd seen I was a contract soldier, they would probably have finished me off on the spot."

"The guards used to beat us a lot more when the Russians were getting their asses kicked at the front"

Roland was sent to a pre-trial detention centre in Luhansk and later taken to a correctional penal colony in Sukhodilsk (this part of Luhansk Oblast has been occupied since 2014).

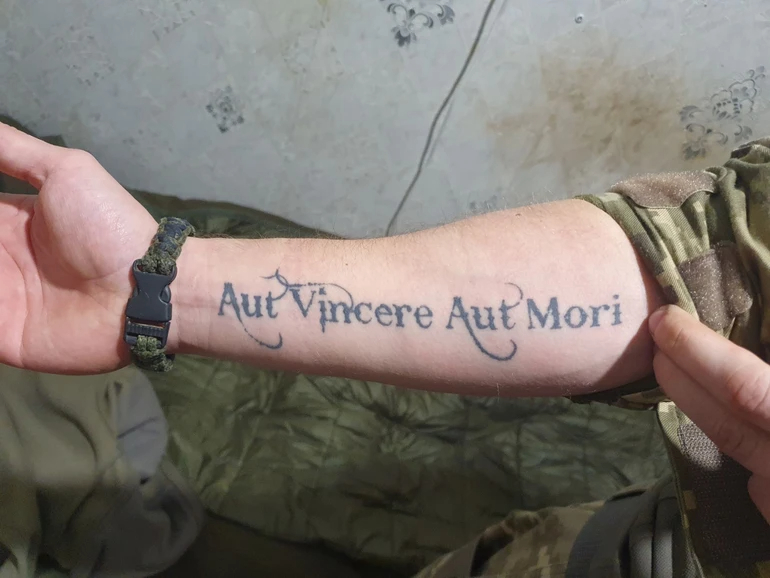

"They didn't touch us during intake, but when they took us to the investigators, they often used to beat us. Especially when they saw the tattoo on my arm, even though it's a neutral one – it's a Latin saying, Aut vincere aut mori (Victory or death). I had it done back in 2021."

Around 500 Ukrainian prisoners of war were being held in the penal colony at that time. There were ordinary criminals serving sentences there too, but they were in a different sector.

"The routine was like this: in the morning you get up, have breakfast, line up for roll call. Then some of the prisoners would be sent to work within the colony (sewing, or working on machines), and the others would sit in the yard. The food was bad, especially at first. They often gave us plain boiled cabbage, which was hard to eat – even our pigs are fed better. Later it got a bit better – we started getting porridge, and potatoes.

The guards were locals from Luhansk. Their treatment of us varied. Some didn't touch us and might even offer you a cigarette, but others would beat us for no reason – 'as a preventive measure'. The general rule was, they beat us a lot more whenever the Russians were getting their asses kicked at the front. I don't want to give any more details in case it harms the guys who are still there…"

In their free time the prisoners could borrow books from the library (a special guard was also sent there). The old stocks still included some literature in Ukrainian, which in theory could also be requested. But if the guards saw any Ukrainian books, the prisoner would definitely pay for it.

"I took out books about the Second World War, and I also read Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne. Sometimes we were allowed to watch TV, usually Russian news. And we could see that when foreigners were commenting on events, the Russian translation dubbed over it would be giving its own version, not a literal interpretation," the soldier recalls.

The men would hear real news from the front line when newly captured prisoners arrived at the penal colony. That was how they learned about the Kharkiv and Kherson counteroffensives by the Ukrainian defence forces in autumn 2022, during which the Russians were significantly pushed back.

It was impossible to send relatives any word from the colony, but Roland's parents knew where he was because the Russians posted several videos on social media – one filmed at the moment he was captured (that one was not posted immediately, but some time later), and another, featuring other prisoners as well, from the penal colony.

After a year in captivity, in June 2023, Roland was summoned for another interrogation, during which two men told him that because he was of Hungarian origin, he might be included in an exchange (the specific word "exchange" was used). They asked Roland whether he agreed, and naturally he said he did. He knew nothing about the initiative by the Hungarian religious organisation or the Russian Orthodox Church.

"They put me back in the colony, and a few days later the guards called out several surnames, including mine, and ordered us: 'Get your things and go to the exit.' They put us on a bus and took us in an unknown direction; they picked up several more prisoners along the way from other penal colonies. There were 11 of us altogether, mostly from Zakarpattia, but not all – at least one guy was from another oblast," Roland says.

On what principle the group of prisoners was selected remains unclear. The Hungarian religious charitable organisation (the Order of Malta Charity Service) insisted that the Ukrainian servicemen released on its initiative had to be ethnic Hungarians. But in fact, of the 11 men, Roland is the only one who has Hungarian roots, through his father, and can speak Hungarian.

The prisoners were taken to Moscow; for part of the journey they were blindfolded and had their hands tied. When the bus finally stopped, they were ordered to sit in silence with their heads lowered.

"Then the blindfolds were taken off, our hands were untied, and we were ordered to get off the bus. It was an airfield. Some Russian priests came up to us, and a group of Hungarians joined them. Everyone stood in a circle and prayed. After the prayer the Russian priests handed each of us an icon. Then we were put on a plane, and as soon as it took off, the Hungarians told us through a translator: 'That's it – you are now free people!' They gave us clean clothes and brought us proper food. It was 8 June 2023, and I had been in Russian captivity for one year, minus two weeks…"

A few hours later the aircraft landed in Istanbul, and the former prisoners were flown to Budapest that same day.

"My parents didn't want me to come back to Ukraine, and some of the other lads' parents felt the same. I can understand why"

Neither Hungary nor Russia officially informed Ukraine of the release of the 11 Ukrainian POWs. Kyiv learned about it from a press release issued by the Russian Orthodox Church, which claimed the release had taken place "as part of inter-church cooperation at the request of the Hungarian side".

As soon as the release sparked public attention, Hungary's Deputy Prime Minister Zsolt Semjén, who is also the Minister for Nation Policy, Ethnic Policy, Church Policy and Church Diplomacy, told the Hungarian media that he had personally coordinated the process, emphasising that it was his "human and patriotic duty".

However, other Hungarian officials insisted that the release had been the result of consultations between charitable and religious organisations, and that Hungarian state institutions had had no involvement whatsoever.

The Geneva Convention allows POWs to be transferred to a third country (which must also be a signatory). This in itself is not unusual. However, any such transfer must be conducted with the knowledge and consent of the POWs' country of origin. Since this requirement was not met, suspicions arose that the release of the Ukrainian POWs might have been part of a special operation or even a provocation.

Several strongly-worded statements were issued by Ukrainian officials, including Foreign Ministry and Defence Intelligence representatives. They said: "The former POWs are in complete isolation in Hungary and have no access to open sources of information. They are only allowed to speak with their families in the presence of third parties, and attempts by Ukrainian diplomats to contact them directly have been unsuccessful."

Ukraine's Human Rights Commissioner Dmytro Lubinets also stated that "Hungary is preparing a psyop so that it can accuse Ukraine of being unwilling to exchange prisoners with Russia."

He added that Hungary was restricting the Ukrainian POWs' movements and ability to communicate and denying Ukrainian diplomats access to them.

"They are effectively being kept in isolation, they have no access to open information, contact with family members takes place in the presence of third parties, and they are denied contact with the Ukrainian Embassy. Attempts by the Ukrainian side to establish a constructive dialogue with the Hungarian authorities through official diplomatic channels are, sadly, being ignored," the Ministry of Foreign Affairs said at the time.

This is how Roland remembers that time: "We were housed in a residential area with everything we needed – kitchen, washing machine, shower. They gave us the chance to call our families. I was so nervous I forgot one digit of my mum's number, but I quickly remembered it. My family already knew that I was free and in Hungary.

I invited my mum to visit me, and a few days later she came to Budapest. She lived with me in the same house – there were spare rooms.

The other lads' families came too. The Hungarians provided everything we needed – clothes, toiletries, cigarettes. They brought us cooked meals every day and gave us pocket money. Right from the start we were free to go outside for a walk or to the shops, to speak with our families, to make calls. No one controlled us.

No one ever suggested, either publicly or privately, that we should criticise Ukraine or praise Russia. As soon as we arrived in Budapest, they repeated again that we were free people now and could do whatever we wanted – stay in Hungary, go home, or contact the Ukrainian Embassy."

The first group – three former POWs – returned to Ukraine on 20 June, just 12 days after their release and arrival in Hungary. Gradually others went back too – anyone who wished to.

In Russia, they had been forced to sign a document before being released stating that they would not return to Ukraine until the war was over, but none of them felt bound by that.

Roland stayed in Hungary for about a month, then obtained the necessary documents at the Ukrainian consulate and travelled back to Ukraine without any obstacles. However, the men's families did not always encourage them to return.

"My parents didn't want me to, and some of the other lads' parents felt the same. I can understand that – who would want their child, after captivity, to return to a country at war? But Budapest is only 300 km from Zakarpattia – just a few hours' drive – and I just couldn't not go home.

I did like Budapest a lot, especially the embankment and the Danube (it was actually my first time in Hungary). And I'm grateful to the Hungarians for my release. If it hadn't been for them I might still be in captivity, like some of my mates. And who knows what could've happened in that time," Roland says.

After returning to Ukraine, Roland was sent to a military sanatorium for rehabilitation. He was still a member of the 10th Mountain Assault Brigade, so after the rehabilitation treatment, he went back to his unit. He was presented with the Commander-in-Chief's award For Unbreakability (an award for soldiers who were held captive) and the medal For the Defence of Ukraine (a state award from the president).

The brigade's command tried to protect the former captive – they didn't send him on combat missions and kept him away from the line of contact, which is understandable. But Roland didn't like this level of "care", so as a former POW he exercised his right to discharge himself and went home for a break. He got two more tattoos during that time, including a trident on his neck.

"I spent a few months just having a rest," Roland says. "Sometimes I drank, to be honest. We all drank..."

Later, to everyone's surprise, he decided to return to the Armed Forces and signed a contract with the 128th Zakarpattia Mountain Assault Brigade.

"My family weren't happy that I went back to fight. But I'm an adult and it's my decision," Roland adds.

"Captivity changed my attitude towards the Russians. My hatred has turned into contempt"

Roland now serves in an artillery unit in the 128th Brigade, operating a 2S1 Gvozdika self-propelled artillery system. He is actively fighting, spending most of his time at combat positions, and has suffered concussion from nearby missile strikes.

"Just the other day we were repelling a Russian assault with constant fire on the enemy. And they were hitting us too. Recently an enemy FPV drone struck the hull of a vehicle and we had to leave the position. I pushed the self-propelled artillery so hard it even 'took its shoe off' [the track came off], but I managed to get it to the next wooded area. We saved the vehicle. And ourselves…"

Roland keeps in touch with his former comrades – both those who were released via Hungary and those who remained in the Sukhodilsk penal colony and were exchanged later.

"We call each other from time to time and share news. There's another former POW who has also come back to the Armed Forces – I don't know about the others. But it's up to them to decide what to do next."

Roland admits that captivity has changed him.

"I've definitely changed. I don't sleep properly like I used to anymore. But I've got more patient. I learned that there – you had to endure, wait and hope. At first, after I was released, I kept having dreams about the war. But strangely enough, I've never had a dream about the penal colony..."

The other 11 former POWs have met with various fates. One died of an illness after returning to Ukraine. Others have stayed at home or gone abroad. As former POWs, they have the legal right to leave the Armed Forces and to travel freely outside Ukraine.

The full details of the release of the 11 Ukrainian POWs in June 2023 remain unclear. Since Hungary was involved, and Budapest is known for its pro-Russian rhetoric and for blocking Ukraine on multiple fronts (from EU integration to military and financial assistance), there are suspicions that this may have been a special operation or a provocation.

But there are far stronger arguments in favour of this having been a straightforward humanitarian mission. The mission's main flaw was the lack of coordination with Ukraine, but its advantages were substantial.

Eleven Ukrainian soldiers returned home without an exchange – Ukraine did not have to hand over Russian POWs. The men are now free to decide their own future (with the exception of the soldier whose health deteriorated in captivity and who died after his release).

Russia, meanwhile, gained nothing. That is likely why there have been no further releases of Ukrainian POWs under the scheme. If anyone in Moscow had hoped to extract propaganda value or any other benefit from this "psyop", the result was the exact opposite. The only one of the 11 former POWs who actually has Hungarian roots considers himself Ukrainian, has returned to the Armed Forces of Ukraine, and continues to fight against the Russians with the 128th Brigade.

"Captivity changed my attitude to the Russians," Roland says. "At the start of the full-scale invasion, I felt hatred when I saw what they did in Kyiv Oblast. Now, I feel contempt."

Author: Yaroslav Halas, specially for Ukrainska Pravda. Life

Translation: Anastasiia Yankina and Tetiana Buchkovska

Editing: Teresa Pearce