Hitting the rear and easing the load on HIMARS: Ukraine’s new mid-range drones

HIMARS (High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems) are a household name in Ukraine. The US-made multiple-launch rocket systems are a key weapon for hitting 30-120km-range targets. HIMARS are used to destroy logistics routes, ammunition depots, command posts, air defence systems, electronic warfare equipment and more.

But they have their weak points too. The Russians have started jamming HIMARS rockets with electronic warfare systems, as well as camouflaging their own positions more effectively and locating them further from the front line. The rockets themselves are in short supply because they are supplied by the United States.

This has forced Ukraine to seek alternative means of attack that can reach the same distance with comparable accuracy.

Ukrainian weapons engineers therefore began working on what they call "middle-strikes" – mid-range drones that can be controlled over tens or even hundreds of kilometres and can carry various types of warhead weighing up to 100 kg.

The mass deployment of such drones would allow Ukraine to replicate, at least in part, the "HIMARS effect" and hit Russian command posts, logistics and equipment even deeper in the rear. This would push Russian forces further back and reduce offensive pressure on the front line.

Mid-range strike drones are still in short supply within Ukraine's defence forces, although Ukrainian manufacturers have now learned how to produce them. Oboronka reports on how this new type of drone emerged and how it is being used against Russian forces.

Mid-range strikers on the front line

The emergence of mid-range strike drones has been driven by the rapid growth of Ukraine's drone sector. As the name suggests, this type of UAV sits between a short-range FPV drone and a long-range drone capable of hitting strategic targets hundreds of kilometres away.

The key difference between mid- and long-range strike drones is that the former maintain a live connection, while the latter are guided to their targets solely by GPS. This means that mid-range strike drones can stay in contact with the operator, be guided visually to the target, and confirm the strike.

Although mid-range drones operate at a shallower depth than long-range strike drones such as the FP-1 or the Liutyi (Fierce), they are more technologically complex. To work in harsh frontline conditions, mid-range drones must have terminal guidance modules, additional types of communication, and navigation systems.

Creating a communications channel that can operate at ranges beyond 30 km has been one of the main challenges for Ukrainian developers.

Priority targets for mid-range drones are command posts, logistics hubs, electronic warfare and electronic intelligence (EW/ELINT) assets and air defence systems located dozens of kilometres behind the front line.

"Russian forces in the strike zone are well camouflaged and dispersed. A mid-range strike drone allows us to hit them where they don't expect it and where they are concentrated," a representative of a major Ukrainian drone manufacturer told Oboronka on condition of anonymity.

Reports about mid-range strike drones first appeared in 2023. The main operators were Defence Intelligence of Ukraine (DIU), the Special Operations Forces and the Security Service of Ukraine. At that stage there was no talk of them being used extensively.

Detailed reconnaissance is carried out before the drones are deployed. Once the target location is confirmed, its coordinates are passed on to the operators to strike.

There will usually be layers of Russian electronic warfare systems and air defence along the route to the target, plus the more recent addition of interceptor drones.

This forces drone operators to fly lower, which increases the risk of losing the connection with the UAV. For this reason, such systems are often launched in tandem with a reconnaissance drone, usually a Shark or Leleka (Stork), which relays the signal and can carry out additional reconnaissance of the target.

There are various reasons why these capabilities were not developed in 2024, ranging from the lack of high-quality drones on the market to low interest from the General Staff.

A source in the defence forces involved in this sector's development told Oboronka that full-scale work on mid-range strike drones only got going in autumn 2024. Up until then, the state had paid no attention to developing or procuring them.

It wasn't until nearly 2025 that they started to be used more or less regularly. (According to Vadym Sukharevskyi, then commander of Ukraine's Unmanned Systems Forces, over 400 of these drones were used in April and May.)

Now, according to the military personnel and analysts Oboronka spoke to, the situation has significantly improved. An officer with the alias Falco, from the 14th Separate UAV Regiment of the Unmanned Systems Forces, told Oboronka that mid-range strike UAVs are now a separate class of drones within the defence forces. Brave1, a Ukrainian defence tech cluster, has also reported high demand for this type of drone.

Although only the General Staff has precise figures on the use of mid-range strike drones, OSINT analysts and military personnel say they have been deployed on a regular basis.

The experts interviewed by Obronka have different opinions regarding what range or warhead weight a drone must have to be classed as mid-range. Presumably Ukraine uses different mid-range strikers for different tasks, and their specifications vary accordingly.

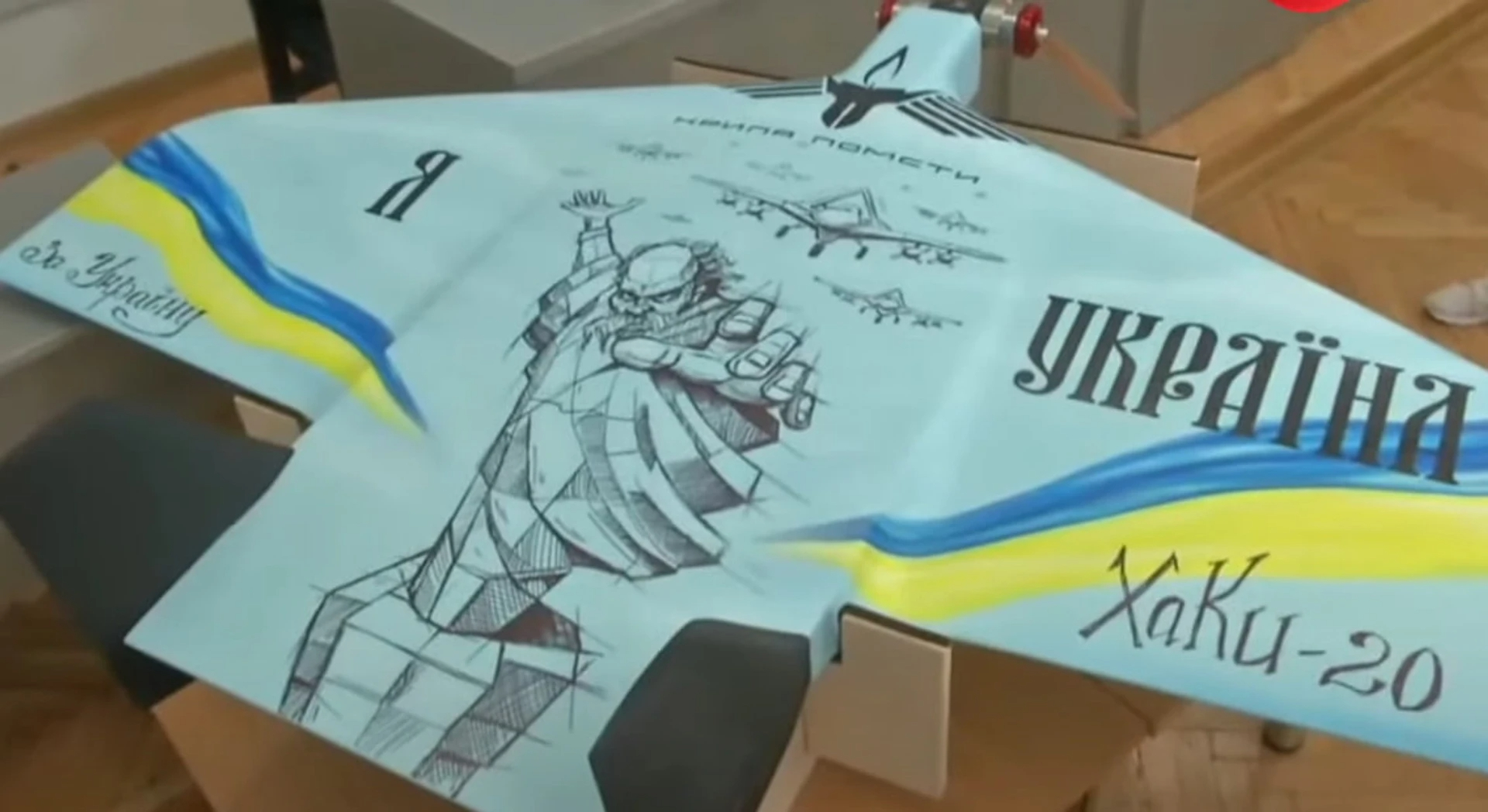

Strikes by Rubaka (Slasher) / Khaki drones have become a regular occurrence in Crimea and Donbas. These UAVs can fly up to 200 km and carry warheads weighing several kilograms. DIU's special Prymary (Phantoms) unit has used them to strike Russian radar systems, air defence systems, and even helicopters and aircraft.

Ukrainian Bulava (Mace) and RAM-2X drones are used at ranges of up to 100 km. They are fitted with terminal guidance systems, have high manoeuvrability, and carry relatively small warheads (up to 5 kg). They are used to destroy air defence and radar assets.

Drones that previously flew thousands of kilometres have also begun to be used for strikes at operational depth. "Right now there's a certain conversion of long-range to mid-range going on," one Ukrainian manufacturer said. "Communications systems and automatic terminal guidance are being added, fuel tanks are getting smaller, and the warhead is getting bigger."

One example of such a conversion is the FP-2 drone, a reworking of the longer-range FP-1. It now flies not 1,000 but 200 km, yet it can carry a warhead of up to 100 kg. These drones are used to destroy large or well-fortified targets.

But the FP-2 isn't the only drone to have appeared in the mid-range segment. According to the creator of the OSINT analysis Telegram channel Potuzhnyi Informator (Powerful Insider), which analyses the use of drones on the front line, you can find the remains of a vast number of different drones that were used to strike the Russian rear.

These include the propeller-driven UJ-26 Bober (Beaver), the jet-powered Skyline-300, and loitering munitions such as Peklo (Hell) and Bars (Leopard).

In addition to Ukrainian-made systems, foreign-made drones are also used, such as the Phoenix Ghost, Dagger, Disruptor and Outlaw G2. Almost nothing is known about them.

Meanwhile, Russia has also been building up its capabilities in this area to counter Ukrainian mid-range strikers.

The Russians began to develop their own mid-range strike drone as long ago as 2019. That was when they created the Lancet – a kamikaze drone that can fly up to 100 km and has a warhead weighing around 3 kg. Since 2019, these drones have received improved communications and several different types of warhead.

The Russians have produced several more drones of this class since then, including the Italmas, KUB-2 and Izdeliye-53. In 2025, they began using long-range series-"Ъ" Shahed-type drones equipped with cameras and radio control.

"These new series-'Ъ' Shaheds are Russia's main mid-range strike drone, and they are strengthening this component very effectively," the creator of Potuzhnyi Informator told Oboronka. "Their strikes on the railway alone prove their worth."

To increase the effectiveness of the strikes, the drones are accompanied by reconnaissance systems such as the Superkam, Orlan-10 and Zala.

Overall, the Russians' approach to developing and using mid-range strike drones can be summed up as "cheap and plenty", and it's a strategy that's proving effective.

"They take a systematic approach," Ihor Lutsenko, a serviceman and aerial reconnaissance operator, told Radio Liberty. "If an asset is good, the Russians scale it up by the thousands and constantly try to improve it."

Unlike the Russians, Ukrainian manufacturers and the military focus on more technological solutions, designed so that destroying a target requires only a few drones, not dozens. This is partly due to a lack of resources.

The need to scale up

Ukrainian manufacturers are not currently able to fully meet the military's demand for mid-range strike drones.

To provide Ukrainian forces with more mid-range UAVs, Brave1 has made their development one of the priorities of a new grant programme. The main objective is to partially replace multiple-launch rocket systems, particularly HIMARS.

Developers are tasked with creating an effective UAV suitable for mass production, so cost and scalability are the key criteria.

But the ability to scale up doesn't just depend on the number of manufacturers – which, according to Falco, are sufficient on the market for every need. It also depends on state procurement.

"Here, as in many other areas, those who have the money are the ones who make most use of it. Whether that's good or bad is hard to say, but coordination between organisations is often lacking," says Vadym Hlushko, founder of the OSINT community Cyberboroshno.

The lack of government orders for mid-range strike drones is an issue that has already been raised among the military. Oleksandr Karpiuk (also known as Serge Marko), a serviceman in the unmanned systems battalion of the 59th Separate Motorised Infantry Brigade, said in a Radio Liberty report that the state had not purchased any such drones.

Deviro, which manufactures the Bulava reconnaissance strike system, was one of several companies that ran into procurement problems at the start of 2025.

"The previous government contracts had ended, and no new ones were coming in. There was a time when we produced a particular batch of Bulavas for stock, because the military had assured us that the money would be provided," Deviro's press service said.

Deviro then decided to give the drones they had manufactured to specialised units free of charge to train crews on and enable them to build up skills in operating the system.

In the end the company did not receive a government contract for the Bulava, but funding was obtained from partner countries.

Another challenge for manufacturers was creating a standardised warhead for mid-range strike drones. "Creating an effective munition that weighs 40-50 kg isn't just a matter of stuffing explosives into a tube; it requires a scientific approach," one Ukrainian drone manufacturer said.

Brave1 revealed that they launched the production of standardised warheads two years ago to solve this problem. Since then, around 50 manufacturers of UAV munitions have emerged, and more than 250 codified types.

Yet despite the number of producers, the situation with warheads remains patchy: amid the wreckage of downed mid-range strike drones, you'll often come across Soviet munitions that have been adapted for use on UAVs.

The servicemen Oboronka spoke to gave various different answers when asked about the situation regarding drone munitions, so the picture is mixed.

You cannot simply stuff a drone with large munitions – a balance needs to be struck between the drone's warhead and its cost. Increasing the payload directly affects the price of a drone due to the need to install a more powerful engine and a different airframe design.

Alongside the production problems, threats on the battlefield haven't gone anywhere. Currently the main threats to mid-range strike systems are Russian electronic warfare systems and interceptor drones. Falco says work is underway on both tactical and technological levels to counter them.

For example, one of the most obvious tactics against interceptor drones is to fly at ultra-low altitudes, hiding from drones and radar – but this requires better communications systems.

On a technical level, this problem can be solved by fitting protective controlled reception pattern antennas (CRPAs), which ensure a stable connection, and using auxiliary equipment.

"Manufacturers will be forced to make changes, otherwise nobody will buy their products," said "Rysak", the commander of a strike UAV company in the reconnaissance battalion of the 13th Khartiia Brigade of Ukraine's National Guard.

Ukrainian mid-range drones have already come a long way. While the first models featured cheap components (communications, camera, GPS) and materials, meaning more drones were needed to destroy a single target, subsequent versions have better components and multiple types of communication and control systems. This allows them to fly further and strike with greater precision.

An ambitious goal

The development of mid-range strike systems is closely linked to the Unmanned Systems Forces, which, according to its new commander, Robert "Magyar" Brovdi, is tasked with covering the front line on three levels – tactical, operational and strategic. To this end, there are plans to increase the number of crews and drones on the front line.

The aim is to expand the "kill zone" – the area in which any movement of infantry or equipment risks destruction. The kill zone is not uniform: depending on unit capabilities, it can be roughly 5-15 km deep on each side.

Beyond it stretches the "grey zone" – an area where movement does not guarantee instant destruction but carries significant risk. It is in this space that mid-range strike systems can operate.

Including mid-range strike drones in the kill zone still seems a radically ambitious objective, Brave1 says. For now, mid-range strikers remain a "surgical" tool for hitting costly high-priority enemy targets.

But drones alone are not enough to achieve the required effect.

What's needed is a combination of different assets and the production of tens of thousands of mid-range strike systems per month. The military and manufacturers now face the task of creating a system that will enable large-scale and systematic strikes to be carried out, maintaining pressure on the Russians.

No one knows how long that will take, but according to Falco, mid-range strikers have already become part of the systemic process alongside reconnaissance drones, interceptors and EW/EP measures.

"If we can produce at least 1,000 airframes a month, and we have, say, 10 crews using them systematically, that could significantly weaken the Russians' entire logistics," the source from the defence forces concluded.

Translation: Anastasiia Yankina and Ganna (Anna) Bryedova

Editing: Teresa Pearce