Artist Ai Weiwei: Democracy and freedom do not necessarily enable the creation of great art

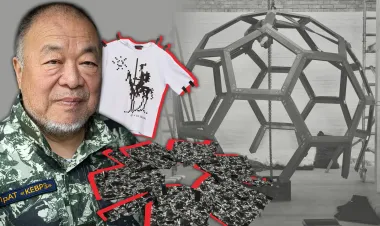

In September this year, Pavilion 13 at the ExpoCentre of Ukraine in Kyiv will open an installation by Chinese artist Ai Weiwei entitled Three Perfectly Proportioned Spheres and Camouflage Uniforms Painted White.

Ai is one of the most world-renowned contemporary artists. In 2011, Time magazine included him in its list of the 100 most influential people in the world, calling him the embodiment of China's hope for the world. That same year, the British art magazine ArtReview ranked him first among the 100 most influential artists in the world.

This is due not only to the work of this conceptual artist but also to his public activities. Ai Weiwei is not one of those who believe that artists should stay out of politics. He publicly criticises the Chinese government for human rights violations and closely weaves political elements into his work.

In an interview with Ukrainska Pravda, Ai admits that he could have come to Ukraine many years ago, but at that time, he was prevented from doing so by persecution from the Chinese authorities. In 2022, he became one of 350 cultural figures who signed an open letter to politicians calling for resistance to "Putin's aggression". This year, he finally made it to Kyiv to create his first work dedicated to Ukraine.

Censorship solely protects the rights of the governor or powerful elites

Let’s start with the project you are doing in Kyiv. What drew you to accept the invitation to create a work in Kyiv during active wartime?

Well, this is my first time in Kyiv, but it is not the first time I have received an invitation. About 15 years ago, I received an invitation from the Pinchuk Foundation. They asked me to be a jury member for the Future Generation Art Prize. At the airport, before I got on the plane, I was stopped by the secret police who said: "You can never travel". So, I missed the chance to come to Ukraine that time.

Then, about two years ago, a friend [reached out to say to me that they] really wanted me to do an exhibition in Ukraine.

I was hesitant, honestly, because at that time, there was a lot of attention on Ukraine, and a lot of people [visited]. They, you know, make big news and stuff like that. But after two years, it got quieter. The war was still going on and even became quite extreme.

I accepted the invitation, and, you know, we are preparing a show at Pavilion 13, which is organised by RIBBON International [a non-profit platform that supports historical and contemporary Ukrainian art and culture – ed.]. I think they are sincere and professional, so that's why I came. But I always wanted to come.

At the beginning of the war, on 24 February 2022, which happened to be my son's birthday, I was very surprised that Russia invaded Ukraine. And what I vividly remember is when a Ukrainian lady talked to Russian soldiers, "During the fight, put some sunflower seeds in your pocket, so next year there will be sunflowers that come up". [Ai Weiwei is referring to a video with a woman in Henichesk, Kherson Oblast, who approached a Russian soldier and told him to "take these seeds, so sunflowers grow when you die here".] That, for me, is poetry. It's very crude, but it's beautiful because it reflects hope and the future. [The] war is going to be over. It may last for years, but still, the war will be over.

So, I think it's the right moment to contribute my work to Ukraine and to make people understand that the war, even if it's so crude, should not last. There would have to be a better life, a better future to look forward to.

[BANNER5]

Can you maybe speak a bit more about the concept of the work itself that you are preparing?

It's very hard to describe the work. But it has to relate to my personal history, to art, to what art is about, and to the current situation.

If we talk about the structure and the material, the work is structured into three spheres: large, medium and small. The large one is about 6 metres, and the small one is about 4 metres. They are connected and covered by what looks like military clothes. It looks like military clothes, but it's all designed by me; the fabric is made by me. [The pattern includes] images of cats – the cats we rescued for years.

As we all know, war is about sacrificing human life. No war can be really justified, because we all lose [people’s] lives. But in many cases, we have to fight, to defend. But in every war, animals are also hurt, because they also live.

So I used the animal motif, and made this military-like camouflage. And I made all those military clothes, suits, jackets and pants. And we'll cover these three spheres [with them]. Yeah, that's how I can describe it. And all the military clothes are buttoned up on the spheres and painted, covered with household paint. Just roughly painted.

That's not the first time that you have incorporated painting over objects. [His 1995 work Whitewash involved painting white over ancient Chinese Neolithic pottery, literally erasing historical patterns and cultural markers – ed.]. How do you see the relationship between the whitewashing of history and the information control during wartime? There are many talks about censorship and self-censorship during wartime.

It's a good topic to talk about. You're right, it's not the first time I've used one layer of paint to cover the objects. But this is the first time I used one layer of paint to paint over camouflage, which is quite ironic, as the camouflage is trying to hide or trying to cover.

We are living in a world where there's authoritarianism, and there's censorship. When there's power, not necessarily just in the authoritarian state, but also in the democratic states. There's a lot of censorship. Censorship solely protects the rights of the governor or powerful elites. But it erases the truth and also twists the truth for the public, which has the right to know everything. So we are living in a world like this. This is no exception.

Also, I wanted to ask about Pavilion 13 itself because it's a Soviet space. How important was the historical context of this location? There are certain problems related to the Soviet-era environments in modern Ukraine.

It is very problematic because history always contains sorrow and unhappy moments. No matter if it's personal history or national history. So there are very different ways of dealing with it. I think changing it with contemporary activities is the only way to give the right interpretation of what happened in the past.

[BANNER1]

Globalist universalism is a new vocabulary of new colonialism that erases our memory

I also wanted to ask you about one of the previous exhibitions about Don Quixote , because this is how we reached out to you . I read that the image of Don Quixote is important to your personal history. What does it represent for you?

It represents passion, imagination, sometimes madness, but still, for me, an individual's will. This figure is very fascinating to me because it's trying to achieve the impossible. So when I did the exhibition in Spain, you saw my, how do you say, exhibition logo. It's made of Lego, which is from Picasso's original drawing. [The fact that Ukrainska Pravda uses this picture] is a coincidence, but it's a nice one, and that's why I like the idea.

In your works (such as the film Human Flow ), you advocate for a shared, universal humanity in the face of the global refugee crisis. Yet, there is a view that this kind of universalism, as an approach, can sometimes risk ignoring the specifics of colonial aggression, where one nation is clearly the aggressor and another is the victim. How do you balance the universalist call for "peace" with the particular demand for justice and accountability? Is there a need to balance that at all through art?

I think it's impossible to balance it, because we are living in very specific conditions and also a specific history. So our reasoning and argument also always have to deal with not just characters, but memory and history. So there is no such thing as total universalism. So-called globalist universalism is a new vocabulary of new colonialism. So with new colonialism, which erases our history and our past and our memory, which makes our life look ridiculous, it really talks about one possibility, rather than respecting the difference.

Recently you commented about the project in Kyiv, and you described this work as a dialogue about war and peace, rationality and irrationality. How do you see art as a medium in this dialogue? What does it mean for you?

For me personally, it's a personal effort. We are all facing this dramatic time, and we see people suffering, people ruthlessly, brutally violating human rights or national rationality, all kinds of rationality. So, for me, I have to keep up my expression, and that's why I make such an effort to do this exhibition.

[BANNER2]

If you think you're already free, you're over

In 2022, I interviewed Timothy Snyder here in Kyiv, and he said that, basically, he argued that Russia's invasion of Ukraine is fundamentally enabled by China, which is why China let it happen through support and refusal to deter Moscow. Given your experience with Chinese authoritarianism and your current work in Ukraine, what's your assessment?

I think that's ridiculous. Of course, I criticise China all the time, because I care about China. China is never my enemy. And if they even have relations with Russia, which is very strategically not to help Russians to deal with Ukraine, in many cases, China also has a very balanced view.

They never really supported Russia's military type of thing. Also, Ukraine has relations with China – a long, long, long history, and a good history. [With such statements], people are obviously trying to divide nations, you know.

The question is how to stop the war. China is constantly saying the war has to be stopped. That there should not be so many casualties and so much international interest in the war. It's too many people interested in Ukraine's resources. As someone from the outside, as a Chinese [person] or the Chinese government, we can see it clearly. So that cannot be good for Ukraine's future.

China is now ranked as the world's second most powerful country. You've witnessed China's transformation from an isolated regime to a global superpower during your lifetime. And what is your overall perspective of the current role of China globally?

I think China has played a pretty balanced role internationally. They never believe any country should interfere with other countries' business. You know, they really do [think] that way. And also they are hoping to develop a possibility for them to rise. Because they gradually are becoming really very powerful. They had to change their whole structure. You know, production structure and trading structure. And we see in China, it's always authoritarian, you know, you cannot argue about that. But still, relatively, China is very stable and has developed very fast.

Well, as you said, it obviously is an authoritarian regime. And how do you think this environment for Asian artists will evolve?

I think you're suggesting something like: an authoritarian state will not have the possibility to make important art, which I don't agree with. Very often, people think that freedom would offer them a better opportunity. You know, the whole West has this kind of narrative, I would say propaganda. Democracy and freedom do not necessarily give you the possibility to make great art. Really important art comes from being against the existing system, the political and cultural system, which we rarely see in the West. So there's no meaningful work coming from the West.

The West just, you know, encourages childish play. "Okay, you're so great. You're so creative." Come on. You know, we are human beings. We have intelligence. We have to focus on humanism, which is a fight for censorship, human rights violations and injustice. And if you think you're already free, you're over. You should not even exist as an artist.

Getting back to the question about China, even as China becomes stronger, it doesn't mean it can get better art or doesn't mean it can dominate art. Art is a miracle. Art has come from the impossible. It doesn’t matter from what state.

[BANNER3]

But you still have to be able to work. You are working all over the globe but not in China.

I think the people who work all over the globe are maybe just commercially successful. They may never produce really good art.

Say poetry – you can create it in jail. You can create it in a labour camp. You can create it on a very happy vacation on the beach. It doesn't matter. It doesn't really say if you're in a labour camp, your poetry is not better than the one on the beach. Art is the same. It's a really personal reflection of the world.

Do you see yourself going back to China at some point in the future?

I think I never left China.

Well, I mean physically, of course.

I physically connect to the universe and to the land, the mountains, and the rivers. Without those, I don't have anything.

I have just one last question. I also wanted to ask for your view about identity, preserving cultural identity through art. Because that's one of the struggles that Ukrainian artists and culture in general are going through. Within the broader context, what is your view on art as a medium of preserving cultural identity?

You made it a little complicated. Art itself is identity. If art exists, then cultural identity is being preserved. But if you don't have real art, then it doesn't matter how you try to protect cultural identity. It's not going to happen. So it all comes from effort.

[During my visit] I've seen many people – from factory production, to drones, to farming, to all levels. And the most impressive is the railroad system. They are doing so many things. It's unbelievable. Every morning, we went to the tracks to see people say goodbye to their loved ones. And every evening, we saw the soldiers wounded being taken back to hospital.

I am deeply impressed with this railroad. The railroad system can be so creative, much more creative than artists. Why? Because they have belief, passion and the means to achieve it, and nothing can stop them.

So in that sense, Russians can never win this war. It doesn't matter how strong you are. It doesn't matter what your argument is. If the other side, like Ukraine, wants to defend itself to the end, nobody can win this war. So I do feel pretty strongly like this.

Andrii Boborykin, Ukrainska Pravda